CAV – The coming of age?

By Jorgen Pedersen, Sector Director of Transport Technologies at SYSTRA Ltd

[Ford dealer Max Gottberg drives his Model T up the steps of the YMCA in Columbus]

As old as I am, I still remember my first conversation about autonomous vehicles, the merits, the risks, the regulations, and the public perception of robot cars. I seem to remember that the conversation quickly disappeared down a rabbit hole with someone asking how it related to Asimov’s laws of robotics.

That was significantly more than a decade ago, and while autonomous technology has moved on considerably since then, we still do not have driverless cars on our roads and highways at the moment. Is the promise of driverless technology pie in the sky, is it just another of those concepts that was ahead of its time, and that is now thwarted by the reality of the world around us?

Over the last decade vehicle technology has moved ahead at a monumental speed, I would wager that most of us now have some level of autonomy in our vehicles whether that relates to lane departure warnings, braking assist, or even a full-fledged autopilot that can now be found on the more progressive vehicles. As of this year 1 in 5 new cars have some sort of electricity plug, either as BEV’s or Hybrids, pretty much all of which come standard with some level of autonomy.

The fact of the matter is that true driverless vehicles have been in testing since 2004 when teams took place in the first DARPA 150-mile challenge. Unfortunately, the furthest they travelled was just over 7 miles where all teams vehicles got stuck on a variety of obstacles. Just one year later in 2005 23 teams took place in the DARPA challenge this time 132 off-road miles and considered to be more challenging than the 2004 course, 5 teams successfully completed the course.

But what does autonomy really mean? At present there are 5 levels of autonomy defined ranging from 0 to 5, where 0, as it implies has no autonomy whatsoever, and 5 is completely hands-off, and does not require a driver to be ready to take control. To put this into perspective at present there are no level 5 autonomous cars available, however there are a number of level 3 and level 4 contenders, where Level 3 provides Conditional Driving Automation and Level 4 High Driving Automation. Both of which require a driver to be at the wheel ready to take over in the case of an unforeseen event. Incidentally Tesla’s autopilot is classed as level 2 automation which provides Partial Driving Automation.

In Aug 2022 the DfT issued a circular, clearing the way for autonomous vehicles to be on UK roads in 2025. However, autonomous vehicle trials have been underway in the UK for quite some time, the latest of which I am aware of is the Autonomous bus trial being undertaken by Stagecoach between Edinburgh and Fife. In 2018 Masdar City in Abu Dhabi launched their first 15 seat autonomous shuttle service, and then in 2021 Abu Dhabi also introduced a driverless fleet of taxis as part of a pilot, which is looking to be expanded during 2023. The two Abu Dhabi pilots mentioned are fully driverless, likewise in China several pilots have been completed and driverless vehicles are now being piloted in 30 cities.

So, I hear you ask, if there are no level 5 autonomous vehicles how can completely driverless vehicles be in operation in other parts of the world? The answer to that question is reasonably simple, climate, safety, congestion, preparedness etc. Level 2 to level 4 automation requires a driver to be present and ready at all times in the event of an unforeseen issue. This can mean anything from a weather-related event to the failure of an on-board system or sensor. Many autonomous vehicles use camera technology to identify the boundary of the road, while reasonably sophisticated that becomes more problematic during a deluge of rain, or perhaps impossible with 5cm of snow on the road. In many areas where these driverless trials are being conducted external climate factors are less of a concern. Many of the trials that are being undertaken are also being undertaken on reasonably wide expanses of tarmac or purpose-built travel ways and with minimal congestion, which do not necessarily mimic the typical driving conditions that a true driverless vehicle would be expected to navigate.

Much of the vehicle testing that has been undertaken has been conducted on highways, which provides a relatively simple reflection of driving when compared to an urban setting such as London, or a rural setting with narrow roads, prohibiting two vehicles from passing safely, and where perhaps the only option is to either reverse, or plant your car halfway into a hedge for other cars to pass. To put this into perspective about 80% of roads in the UK are classified as minor roads, and about 7% are classed as B roads.

None of this detracts from the technological advancements that have been made, while we still have much to learn, each of the pilots and trials that are being undertaken provides us with valuable information and data, enabling us to learn from the pilot to further improve not only vehicle technology but also the infrastructure that is required for true driverless capability.

The one absolute guarantee is that autonomous vehicles are coming, but certainly in the UK for the short-term future those vehicles will require a driver to be available to step in and take control. Given the monumental speed of technological change, and the amount of money that is being ploughed into autonomous vehicle research it’s likely that we will see many more trials of completely driverless vehicles taking place around the world.

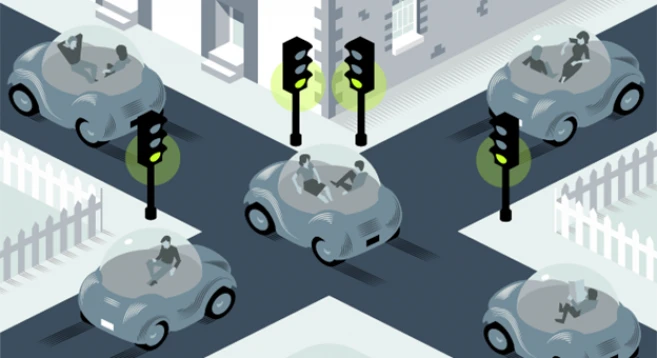

So, when putting together your next Local Transport Plans, it is suggested that Battery-Powered Electric Vehicle (BEV) and Electric Vehicle (EV) technologies should get some emphasis, but so should autonomous vehicle technology and infrastructure. It is proposed that over time, autonomous vehicles could provide on-demand transport services in more rural areas, filling a gap that traditional fixed route services struggle to service and support. In more urban areas autonomous vehicles could provide delivery services to transport goods to retail stores, businesses, and office locations. The introduction of autonomous services in these communities could provide sustainable and ecological friendly services that bring communities together into place setting environments that also foster economic growth.

Written by Jorgen Pedersen from SYSTRA Ltd.